In its Charter for Regional or Minority Languages the Council of Europe declares, “Regional or minority languages are part of Europe’s cultural heritage and their protection and promotion contribute to the building of a Europe based on democracy and cultural diversity”.

Our European heritage is a fascinating palette of languages, oral traditions, and a cultural history embedded within the languages; a richness of peoples and diversity that needs support and protection from the libraries.

Unless all of us embrace the value of preserving this diversity for the future, we will see languages disappear and with them stories, songs and immaterial cultural heritage. Some of the essence of Europe will be lost.

Europe is, and has always been, a multicultural continent with different peoples and languages living side by side. Historical events have divided people on different sides of borders, or been the cause of a people crossing borders. People have moved into territories and pushed others aside, reducing them in numbers. Europe has a long history, starting in ancient times, of peoples, languages and culture moving back and forth over the continent.

During 2020, a new working group within the NAPLE structure saw the light: Library services for, with and by persons identifying as bearer of a Regional or Minority Language.

The very long name of the working group might need some explanation: “for, with and by” opens the possibility for the minorities themselves to be active in the working group. It is of great value for the working group to include participants that belong to one or more groups protected by the European Charter. The working group also includes regional and minority languages equally, coming together to address questions about how libraries can support any language that needs special attention.

Either a low number of speakers and/or a late written tradition makes it hard to keep languages alive. For public libraries, it is a challenge to find literature in these minority languages and to deliver library services to the user groups who speak these languages. Sometimes it seems almost impossible, when the publication rate is one book every second year. The librarian needs to become a magician!

The NAPLE working group have decided on the following six action points:

- Raise awareness.

- Share best practices of strategic planning for library services for the target group.

- Share leadership models, national guidelines, etc.

- Share knowledge about acquisition and the actual purchasing of media in a specific minority language.

- Share knowledge about specific services for national minorities, regional minorities.

- Share knowledge about how to facilitate members of minority groups taking part in decision-making and how to empowernational minorities.

For the moment, most of the work of the working group has focused on the first action point; ‘raise awareness’. The level of awareness varies across participating countries, but we have all agreed to this as the first action.

So far, the working group has hosted a joint webinar with The Conference of European National Librarians (CENL) on “The Role of National and Public Libraries in Engaging Users of Regional and Minority Languages”. The webinar focuses on the current situation in Slovenia, Estonia and of the role of National Libraries.

There are differences between public library services to a diversified and multicultural population and services to national minorities or patrons using regional languages. Of course, most European countries have committed to the Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Still, looking at it from the libraries’ point of view, there are some particular challenges.

Many of the languages the Charter protects are small, with few speakers. Due to the pressure of the majority language, these languages are, in many cases, suppressed and immobilised. – Some are even languages that are “not allowed” to exist. These may be languages only used within a family context or in a specific situation, a specific community. Some users of these languages might not be able to read or write, but can speak their language fluently. This makes it even more of a magician’s task to promote reading, and to find books in the right language and at the right level, for instance easy reading for adults. How can we find ways to encourage kids to have fun with the language; to play with words and learn in a natural way full of joy, despite the lack of resources?

Let us return to the common framework that puts all of this in plain text. The Charter, or, by its full name, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, is the European convention for the protection and promotion of languages used by traditional minorities. Together with the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, it constitutes the Council of Europe’s commitment to the protection of national minorities.

The Charter covers 79 languages used by 201 national minorities or linguistic groups. Some of the languages covered by the Charter are present in many countries.

Sweden recognises five national minority languages: Yiddish, Finnish, Romani, Meänkieli and Sámi.

I will pick some examples from the Charter: the Romani and the Sámi groups.

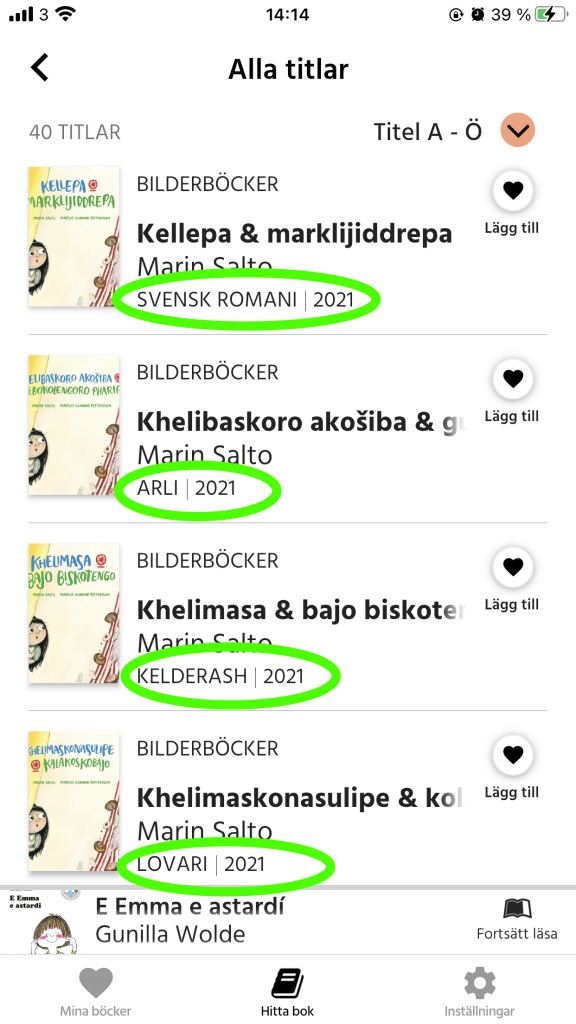

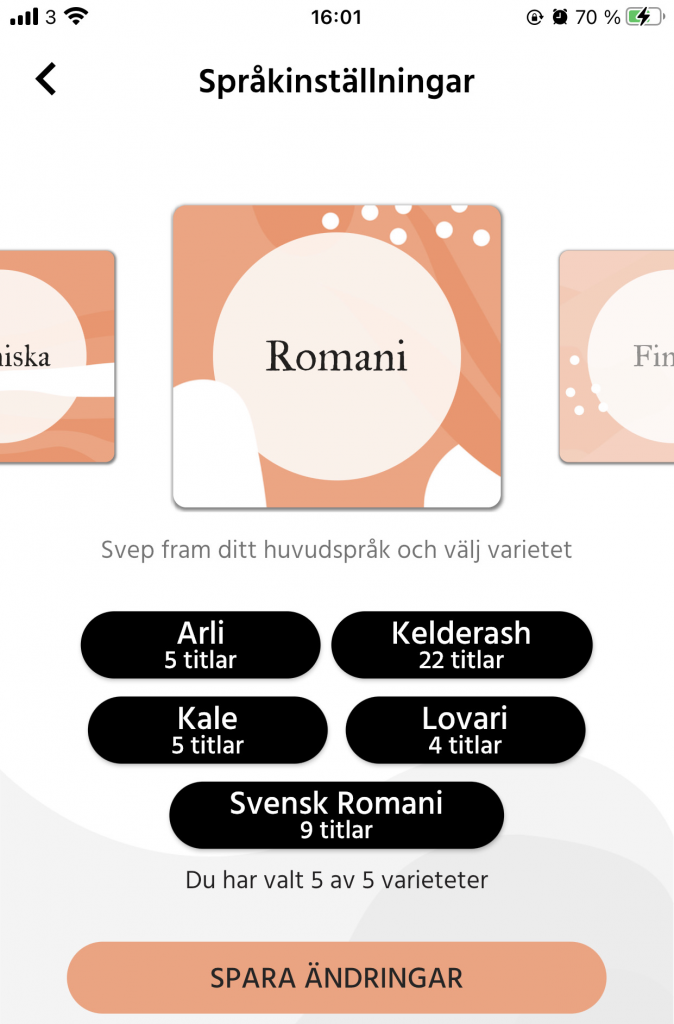

Romani is listed in 16 countries, and Romani people are present in most European countries. The language might be the largest minority language in Europe, but it has over 60 dialects or varieties, and some of these have very few speakers and are on the edge of extinction. One of the most endangered Romani dialects is the Kale Romani, spoken in Finland and Sweden.

For libraries, it is essential to know which of these dialects local users speak. Without that information, the library might purchase books no one will read! The wrong dialect doesn’t promote reading – or improve the speakers’ view of the library!

Modern borders between Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia divide Sápmi, the traditional territory of the Sámi. Some of the Sámi languages are extremely endangered, with fewer than a hundred speakers. The Sámi are also an indigenous peoples and most of their traditional knowledge is embedded in the language. Losing the language also means losing the knowledge. The Charter and the international conventions on indigenous rights gives the Sámi people the right to preserve their language and culture. But how can libraries assist with this?

Jokkmokk is an important place for the Sámi people. Since at least the 13th century, people have gathered there during the winter to trade. Today, Jokkmokk is the location of several institutions, including: an education centre, the Ájtte museum, and an office of the Sámi Parliament, as well as the Sámi library. The collections in the Sámi library run by the Sámi Parliament should be regarded as a national library, a parliamentary library, a research library as well as a library for an indigenous population.

Photo: Elisabet Rundqvist, National Library of Sweden

The public library of Jokkmokk is one of few public libraries with a substantial collection in the Sámi languages. In spite of this, thereis not an abundance of books, as you can see in the picture above.

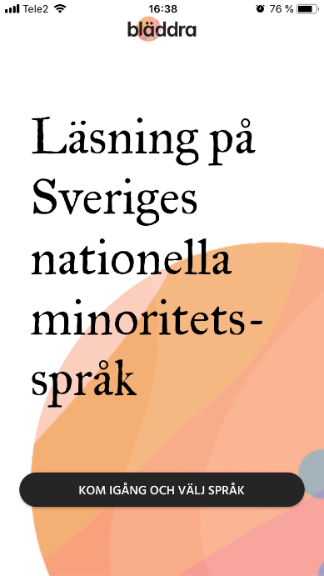

In the spring of 2019, the National Library of Sweden initiated a pilot project to create Bläddra (in Swedish, approximately ‘Browse’).

The objective was to investigate what a national digital library service for literature and reading could offer national minorities. Additionally, it aimed to create a viable but smaller-scaled product with a selection of languages as a start. This would be an ebook reader application giving equal access to books in two national minority languages, all over Sweden.

The foundation of success for this project was the early focus on dialogue and cooperation with representatives for the national minority languages, such as potential users, librarians, native language teachers, authors, etc.

Considering the needs and wishes of potential users and the limits of the project, it was decided to focus on ‘leisure readers’ as the main target group for Bläddra. The project team determined that this user group had much to gain from easier access to books in their own language.

Bläddra is an app with a focus on reading promotion, rather than on language revitalisation. Bläddra was released in the spring of 2021 and is freely available in Sweden. It is an ebook reader app with literature in Romani chib and Sámi, with five variations of each (equivalent to ten separate languages). After downloading the app from the App Store, the user is immediately able to start reading, with no need for a library card or a user account. This is important, as evidenced by the User Experience (UX) interviews, which revealed one common finding: low thresholds to access were essential. Users asked for a direct connection between the reader and the book, without barriers such as a library account.

How can Bläddra be regarded as a tool for libraries when no library card is necessary?

Data gathered by the UX team showed that many of the users never visit a library, but do enjoy reading. Instead of bringing non-readers into the library to promote reading, why not reverse the order? As a first step, promote Bläddra to make readers out of non-readers, and as a second step bring them in to the library.

Bläddra can be used as a reading promotion tool in various ways. Story-time events for children can be arranged using a screen to display pages. That way, participants can simultaneously listen, follow along reading the text, and see the illustrations clearly.

For teachers or a book club in need of a class set of a title, the app is also suitable – everyone in the group has access to the book.

An app can additionally lower any threshold obstacles to reading since it is private. A hesitant reader who wants discretion doesn’t need to visit a library or hold a book in their hand for all to see. It can also serve as a gateway to reading in the reader’s own language.

Public and school libraries can use Bläddra in their own acquisition planning. The books in Bläddra have been selected in collaboration with the representatives of each particular language group, and are available for viewing in the app.

During 2022, a third language will be added: Meänkieli, which is a language spoken by Tornedalians.

I will also share another example from Sweden; a ground-breaking development of national services, supporting the public libraries in Sweden and nationwide services for patrons identifying as members of a minority.

Since 2015, Kungl Biblioteket (KB, the National Library of Sweden) has prioritised fulfilling commitments as stated in Paragraph 5 of the Swedish Library Act, and in particular Paragraph 5, Section 1: “Libraries in the public library system shall devote particular attention to national minorities”.

Public libraries report that the acquisition of collections in minority languages is difficult, that institutions lack the expertise required to deliver relevant services and programs, and that it is a challenge to find personnel to host readings, children’s story-time, and other events in these minority languages.

In 2019, the National Library of Sweden presented a proposal to the Swedish government to introduce special supports to users belonging to one or more of the national minorities, as well as support to public libraries. Four existing libraries – the library at The Finnish Institute in Stockholm, the Jewish Library of Stockholm, the library at the North Calotte Cultural and Research Centre and the library at the Sámi parliament – were found suitable to receive government funding as designated special libraries with a nationwide scope.

In 2021, KB received the government’s assignment corresponding to the earlier proposal. KB was awarded an annual grant of 10 million SEK (approximately 928,000.00 EUR), from 2021 through 2023.

An initial task in 2021 was to make these four libraries more robust and prepare them for the mission of serving as a national resource both for public libraries and for individual speakers of minority languages directly.

But what about the Roma people? There is no such dedicated library today for this national minority group. The assignment remains, and KB is left with the task of suggesting solutions for a future library, designed to meet the user needs of the Roma people.

Throughout 2021, KB conducted several hearings with members of national minority groups about user needs, and a series of sessions with the designated libraries listed above. These sessions also involved the Roma Reading Ambassador, other authorities, and the Sámi Parliament. During this process, users were given ample opportunity to express opinions and share expectations.

From 2022, the four aforementioned designated libraries should be ready to ‘open their doors’ – figuratively speaking, since most of the services are digital – and begin consultative work directed towards the public libraries.

Elisabet Rundqvist, Chair of NAPLE WG Library services for, with and by persons identifying as bearer of a Regional or Minority Language

Executive officer National Coordination of Libraries and special adviser for library services for national minorities, National Library of Sweden.