In Portugal, the reality of libraries in prisons is practically unknown. However, that doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. Since the 19th century, the existence of spaces for reading and learning in prisons has been enshrined in Laws and Regulations. This does not, however, translate into the existence of libraries in the true sense of the word. Parallel to the evolution of the concept of the prison establishment, there is also a new dimension to this type of library. Prison libraries have undergone a profound evolution over time., However, they have not matched the development and new functions of prison spaces. Initially, prisons were presented as institutions of organization and social control and as a moralizing instrument of social relations, where inmates had few prospects for the future. However, over time they were recognized as having a formative role as a central element of the reintegration process. In recent decades, prison libraries have been striving to make up for the lost time. They have been trying to keep up with this evolution and to become one of its key instruments, as support structures for the processes of recovery and reintegration of the inmate. However, despite their importance and as a consequence of the various problems that affect them, the reality of libraries in prisons is practically unknown by society and by information and documentation professionals. In Portugal, like in many countries, most public libraries that have a prison in their region work in some capacity with inmates, but we still need to make the services more official and effective, and strengthen connections.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: A JOURNEY THROUGH TIME

It is in history that one must look for the origin, function, and purpose of the prison system, as a link between law and power. It was Michel Foucault who first carried out this study on the birth of the prison as a penal device and form of punishment, framed in an ideology that conveys the need to identify and punish deviance according to the corrective principle, based on the designs of the historical period in force in religion, in morality, in society, and also in the ruling intellectual class. It has not been chance, nor the whim of the legislator that has made prison the basis and structure of our penal system, but rather the evolution of ideas and the softening of customs.

During the medieval period, jail almost never amounted to the penalty, instead being a way of guaranteeing that the accused went to trial and/or that he served his sentence. In addition to this preventive function, the prison was also used to pressure individuals to honour social commitments related to the payment of fines or debts. Occasionally, prison appeared with a mixed character, coercive and repressive. With the Manueline Ordinances (16th-century Portuguese legislation), prison appears with a preventive character until trial and conviction, and its coercive character becomes less common.

Imprisonment as a repressive penalty was quite rare, although it was anticipated. The Philippine Ordinances (16th /17th-century Portuguese legislation) maintained detention with a preventive and coercive nature. Preventive detention was also provided for and was admitted as in the previous law. It is unknown whether in Portugal in the Modern Period, as in other countries, there was a progressive expansion of the use of prison, and whether there came to be, in the scope of the daily exercise of justice, any supplementary corrective role in addition to the functions of prevention, coercion and repression. António Manuel Hespanha, a Portuguese historian, emphasizes the continuing difficulties in applying preventive or penal measures, such as the use of incarceration, which required logistical means and required the existence of safe prisons, with means of subsistence for prisoners and conditions for the removal of inmates, in addition to all the expenses involved which must be foreseen. Thus, the repression of crime was carried out through expeditious resources, with the use of brutal and exemplary penalties, which, with great economy of means, demonstrated in a markedly punctual way, the force of law and power. It should be noted that at this time, the passage through prison was an attack on the honour, good reputation, and credit of individuals. The importance of this reality added to the sufferings experienced during their stay in prison, sometimes for long periods, may have influenced the judges to often consider the time spent in prison as time spent in prison. Until the beginning of the 18th Century, the systematic use of corporal punishment persisted throughout the world. Michel Foucault takes care of this situation by defining it as “an art of quantitative suffering”, since the body of the condemned is initially exposed publicly. Corporal punishment, exile, the death penalty, forced labour and deprivation of liberty constitute the fundamental landmarks on which the penal classification itself evolves. Hence, the prison is referred to as the result of a political process of control and internal security of society, which places the convict as someone who, at the same time, is subject to punitive power and, above all, is a didactic example for the people, just like a guarantor of law and power. With the French Revolution, the prison sentence emerges as the correct formula for punishment, being able to be graduated and divided almost to infinity and containing not only punitive purposes but also regenerative ones. Following on from the emergence of philanthropists and educational projects, it was believed that prison could transform Man. However, there was a long way to go before prison became the penalty par excellence. This journey which lasted 600 years, in addition to being long and complex, was a poorly known period. At the beginning of the French Revolution, the need to end torture and reserve the death penalty for cases of extreme violence was accentuated. It was necessary to punish but in another way. The evolved and rational man of the 18th century abhors torture and identifies it with tyrannical practices and attitudes. Fundamentally, the reformers of the 18th-century haste to denounce the excess of power and its manifestation through a single man: the sovereign. It is necessary that the sovereign does not reserve for himself an absolute power and that punishment ceases to be an instrument of revenge, becoming instead an instrument of justice.

In the 18th century, the western society sought new forms of repression that would replace the old and cruel punishments of the Ancient Regime, and that would be adapted to the new links between power and the new times. Punishment is identified as the result of a legal procedure that is built on the basis of a logic that only the law can provide. The body is no longer the target of punishment, this being centred on the individual’s soul, which, through reflection, will lead him to reconsider and correct his conduct and habits. It is at the end of the 18th century that some penitentiary models appear based on this new premise of victory of the body over the spirit. Thus, in the transition to the 19th century, there are three strategies related to punitive power: a first, in which the meaning of the body that suffers punishment prevails; a second in which the social game aims to manipulate the social representations of individuals, and a third in which the exercise of punishment is applied using an administrative machine controlled by coercive power. In the 19th century, a new legislation defines the power to punish as a general function of society that is exercised in the same way on all members, and in which each of them is represented. Prison, as a central element of the punitive system, unequivocally marks a period in the history of criminal justice; the access to “Humanity”. So, since the 19th century the prison covers at the same time the deprivation of liberty – seeking the security of society – and the technical transformation of individuals – enhancing the reintegration of individuals, through re-education processes based on the individual’s work occupation.

The 20th century was marked by profound economic, political, scientific and educational transformations that, as a whole, irremediably altered society. The participation of theorists of correctional pedagogy (jurists, pedagogues, doctors and psychologists, etc.) was to try to explain certain social problems within which delinquency was revealed. From the maladjustments and conflicts resulting from these transformations, correctionalist pedagogues were concerned with the issues of crime, the delinquent and society, working on two fronts: one of an individual nature, influenced by the movement of psychophysiology, psychology or psychopedagogy, and the other of a social nature, with the influence of sociology and sociopedagogy, focusing on the relationship between crime and society.

PRISON LIBRARIES IN PORTUGAL

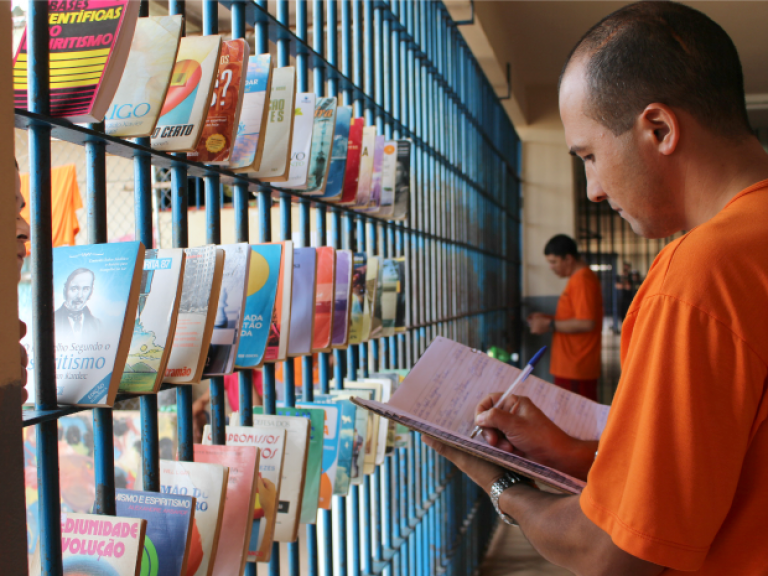

Before presenting the situation of prison libraries in Portugal, it is important to focus attention on issues related to the terminology to be used. Since the beginning of reading the specialized bibliography on this topic, doubts have arisen as to the name to be used to identify this type of library. Expressions such as ‘prison libraries’, ‘reading rooms’ and ‘penitentiary libraries’ made the process of defining the terminology to be used go back and forth. Finally, and after an analysis of the various possibilities – prison libraries, prison libraries or prison libraries – it was concluded that according to the specialized bibliography and in line with the designation used for similar realities (with regard to hospitals, there is also a difference between libraries intended for patients – hospital libraries – and those intended for clinical staff – hospital libraries) it would be more correct to use the designation prison libraries. Since 1901, in the “Regulation of Civil Prisons of the Mainland of the Kingdom and Adjacent Islands ” the existence of “libraries”: “reading spaces (associated with teaching) to be used in the intervals of the offices” is anticipated. However, the first specific reference to a dedicated library space only appears in Law no. 168/80 of 29th May (Directorate-General for Reinsertion and Prison Services (DGRPS) Law), in Article 53, paragraph n). In the revision of the DGRPS law, in 1982, the specific indication of the library disappears, being included in the sociocultural spaces. However, the concern with the spaces destined to be libraries is maintained, attested by the signing of the protocol between the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Justice in 1998. The signing of this protocol allowed the expansion and renewal of the existing collections in the libraries of prison and the carrying out of activities to promote reading in conjunction with other prison and external entities. This protocol also provides for cultural tours in Prison and literary competitions at a national level. It also intends to encourage inmates to participate in activities to promote reading, which, thanks to their success, is increasing in number. As defined in the 1982 Law, these libraries work based on a strong relationship with the teaching activities that take place within the Prison. According to statistical data for 2019, the situation of Prison Libraries is as follows: In 2019, 70 libraries were in operation distributed between the 59 prisons. Altogether, these libraries had around 164,620 documents available for consultation and loan; not including the numbers relating to newspapers and magazines. During the year, 18,677 inmate-readers were registered, who carried out 43,880 loans. From these numbers, it is possible to calculate an average of 2.3 books/year per prisoner-reader. This situation is not far from the one verified in “Portuguese Cultural Practices 2020”, commissioned by the Institute for Social Sciences, as most respondents say they read between 1 and 5 books a year.

With regard to the constitution of the collections available in libraries, it is known that of the 164,620 existing items, 13,450 were gifts (of new copies), and 1,900 were acquisitions. Since all the remaining documents are “heirs of the prison system”, these are for the most part old and outdated documents. Most of the books that reach libraries come from individuals, publishers and the Minister of Culture services. In 2005, prison libraries had a great reinforcement of their collection through the initiative of the Público Newspaper, which offered 200 sets of the “Mil Folhas” Book Collection. However, some public libraries in Portugal seek to assist the prison libraries in their region. For each of approximately 13,000 inmates in 2019, we had an average of 11 books available, which according to the calculations carried out and with reference to international guidelines, gives about half of the 20 books per inmate that are recommended.

The data collected by the DGRSP up to 2019 allow us to characterize the type of prisoner-reader as being male, aged between 20 and 39 years old and attending the 2nd or 3rd school. As for reading preferences, in descending order is poetry, followed by the novel and then comics and the police. In 2019, reading prisoners represented 10% of the prison population. In general, prison libraries are open for less than 10 hours a week. The vast majority are only open 1 or 2 times a week. Taking into account the difficulties of access to libraries and documents by inmates, it is not difficult to imagine that most of them select their readings through catalogues where the title and author are indicated. Although it depends on the type of prison and their spatial-functional characteristics, in most cases the prison library space is also a classroom or social area. In some prisons, the “library” is just a cabinet located in a variably accessible area or a room that can be accessed upon prior request. As Manuel Gutiéz contends, despite the etymology of the word, “a library is not a piece of furniture or a building with books, but a collection of books organized for use”.

COMPETENCIES OF THE PRISON LIBRARIAN

The duties and competencies of the prison librarian are indicated in 3 main documents with guiding principles: the American Library Association (ALA) edited the “Library standards for adult correctional institutions” in 1992, the Library Association (LA) edited the “Guidelines for Prison Libraries” in 1997 and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) edited in 2005 the version of the “International Guidelines for Library Services to Prisoners” (A new version of these Guidelines was presented at the IFLA Conference 2022, in Dublin, but I haven’t read it yet). In addition to more specific skills or skills adapted to the reality of the prison environment, the skills of these librarians are, similar to those of the Public Library librarian present in the UNESCO Manifesto (1994), related to information, literacy, education and culture. Therefore, and in the Portuguese case, the powers contained in Law n. 247/91, July 10th, currently revoked, which used to regulate the career of a Librarian in Public Administration can be considered and applied to this type of special librarian. Thus, if we pay attention to the specific skills of these librarians and the most important references on those documents, we could list the following, as desirable and necessary:

- Emotional balance;

- Dynamic posture;

- Good general culture;

- Adaptability (prison environment);

- Good oral communication;

- Knowledge of languages (depends on the country and context);

- Leadership and supervision skills (work with inmates);

- Interest in working with cultural, ethnic and linguistic diversity;

- Enjoyment of working in adult education;

- Creativity;

- Sensitivity and attention;

- Inventive capacity and abstraction;

- Knowledge of the law and criminal legislation.

If we analyze all these skills, we see that we are looking at a librarian who faces all the challenges and opportunities of those who work in an environment with strong social intervention.

Libraries in prisons are therefore a favourable terrain for strengthening and defining the librarian’s social role, as a mediating and guiding element in accessing information and knowledge. Contrary to what one might initially think, the similarities between libraries in prisons and public libraries are greater than the differences. Due to their condition of reproduction of society, the prisons recreate a micro-society with the same characteristics as the existing one outside the walls. In this way, the prison librarian must have the same characteristics as the professional who works in a library open to the general public. Experience shows that the prison librarian will have a better chance of success if he already has experience in other professional areas such as psychology, sociology, teaching or social work. It will also be convenient that she has worked for some time in other types of libraries, taking into account that prison libraries tend to be more closed, isolated spaces facing the institution. In this way, it is intended that the professional has time to develop contacts with other professionals, carry out training and acquire new knowledge, have contact with other contexts and establish partnerships with other institutions. It is important to understand that not all librarians will be able to work in a prison environment. No matter how much training and monitoring one may have, many characteristics and skills cannot be acquired and/or taught, forming part of the individual profile of each one. All those who work in a prison environment must have a deep understanding of the institution’s purposes and the dynamics of the prison community. They must have the ability to internalize the institution’s basic values while carrying out their duties in an environment sometimes full of ambiguities and paradoxes. Librarians are mediators of information and knowledge and if they don’t have an innate willingness to help, then they may not be in the right profession. In a prison environment, the pressure of “the strongest over the weakest” can be a constant and sometimes unbearable reality.

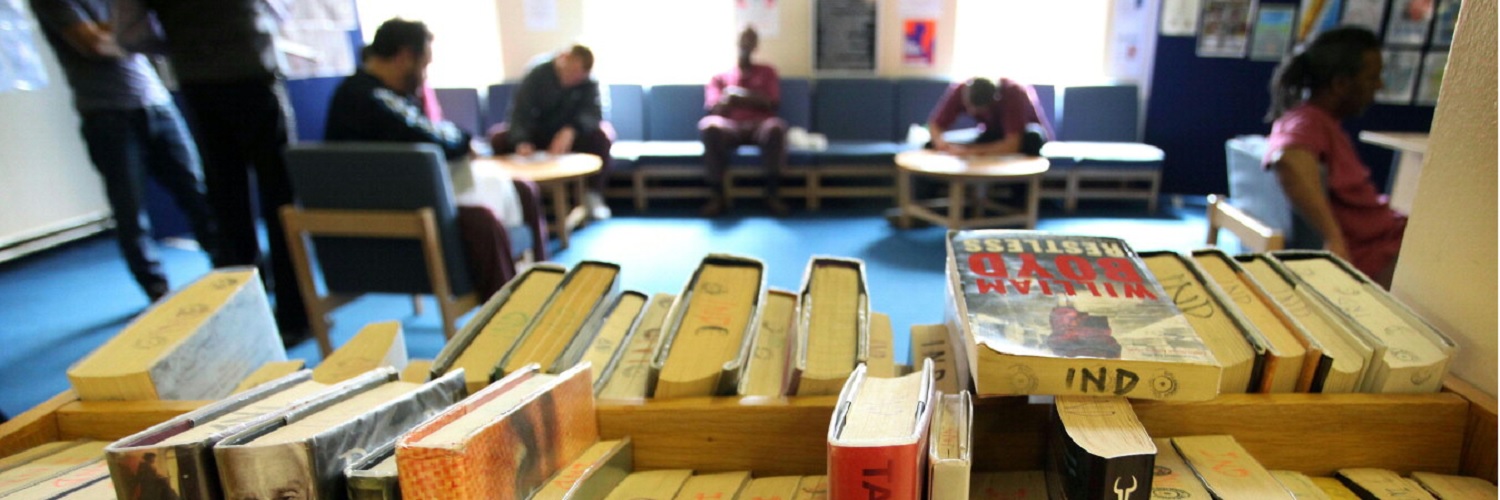

By being available to respond to the needs of inmates, the librarian can gain great importance in their day-to-day, as a compensating element for the imbalances resulting from the prison experience. However, it is not all hardship and there are many advantages and tradeoffs for a competent prison librarian. This professional must be able to achieve these through the provision of specific services and the creation and development of a library that serves the needs of a closed but quite heterogeneous group. Most inmates value the library and respect the work done by the librarian. Many inmates have their first experiences as library users during their stay in prison, so they begin to discover a whole new world of advantages, opportunities and knowledge.

CONCLUSION

Although libraries in prisons have long been anticipated in legislation, the truth is that it has been difficult to create conditions for the installation of this equipment. Although history has proven the benefits of the practice of reading and writing and access to information, the fact is that in recent decades the various attempts made by the entities involved to provide prisons with libraries were not always satisfactory. In fact, these libraries have gone through the same vicissitudes as many others when they are faced with financial, material and human resources problems, to which legal issues, security and access by inmates are added. Several efforts have been made to suitably equip this type of socio-cultural equipment, indispensable in the process of the reintegration of inmates, thus accompanying a new strategic vision of the prison space as a whole.

In general, we can say that:

- In most cases, prison libraries are limited to a room with books;

- They do not have clearly defined opening hours.

- The library space is often also a classroom or social area.

- A library is much more a place of study than access to information, culture and leisure.

- They do not have trained technicians dedicated full-time to working in the library.

In view of the reality of prison libraries, it is important to identify the main functions that they must perform:

- Informal reading spaces.

- Knowledge and self-learning centres.

- Educational support spaces.

- Culture and leisure spaces.

- Legal information spaces.

- Gathering and privacy locations.

- Spaces for social information and reintegration.

- Research centres for Technicians.

Regardless of the operating model to be implemented, it is important to provide all inmates with fair, free and quality access to information and knowledge, whether for their own interest or derived from dynamics external to the prison establishment. However, from the point of view of the social reintegration of inmates, the partnership model allows for greater contact with reality or even allows for the development of socialization and information skills.

If we consider the work of a prison librarian and the role importance and potential of prison libraries, we can easily say that they are a true window into the world.

To know more about:

- CURRY, Ann – Canadian federal prison libraries: a national survey. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. Cambridge. Vol. 35, n.º 3 (2003), 141-152.

- FOUCAULT, Michel – Vigiar e Punir: Nascimento da prisão. Trad. de Lígia M. Ponde Vassalo. 10ª ed. Ed. Vozes: Petrópolis, 1993.

- HESPANHA, António Manuel – Da “justiça” à “disciplina”. Textos, poder e política penal no Antigo Regime. Boletim da Faculdade de Direito. 2 (1984), 139-232.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) – Guidelines for Library Services to Prisoners (3d Edition). IFLA: The Hague, 2005.

- KROLAK, Lisa – Books beyond bars: The transformative potential of prison libraries. UNESCO, 2019.

- LEFEBVRE, Joanne – Lone librarian behind bars: courses offer hope to inmates. Canadian Library Journal. Vol. 45, n.º 2 (1988), 84-89.

- LIEHMANN, Vibeke – Prison librarians needed: a challenging career for those with the right professional and human skills. München: IFLA Journal, Vol. 26, n.º 2 (2002), 123-128. – Planning and implementing prison libraries: strategies and resources. In IFLA General Conference, 69, Berlin, August 1-9 de 2003. IFLANET.

- LITHGOW, Sue; HEPWORTH, J. B. – Performance measurement in prison libraries: research methods, problems and perspectives. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. Vol. 25, n.º 2 (1993), 61-69.

- MILLER, Richard T. – Standards for library services to people in institutions. Library Trends. Vol. 31, n.º 1 (1982), 109-124.

- ONTORIA, Mª Antonia; PÉREZ IGLESIAS, Javier – Servicios bibliotecarios en las prisiones. Educación y Biblioteca. Vol. 85 (1997), 39-65.

- PÉREZ PULIDO, Margarita – Acerca de las bibliotecas de prisiones y sus servicios. Educación y biblioteca. Madrid, TILDE, Vol. 85 (1997), 40-44.

- RUBIN, Rhea Joyce; SUVAK, Daniel (ed.) – Libraries inside: practical guide for prison librarians. [s.l.]: McFarland & Company, 1995.

- RULER, Lies Van – The profile of a prison librarian. In IFLA General Conference, 59, Barcelona, August 22-28 1993, 14-16.

- TABET, Claudie – La bibliothèques “hors les murs”. Paris: Éditions du cercle de la librarie, 1996.

- The Library Association. Prison Libraries Group – Guidelines for prison libraries (2nd ed.). London: Library Association, 1997.

Bruno Duarte Eiras is a Deputy Director General for Book, Archives and Libraries at the General Directorate for Book, Archives and Libraries, Ministry of Culture, Portugal.